About this Project

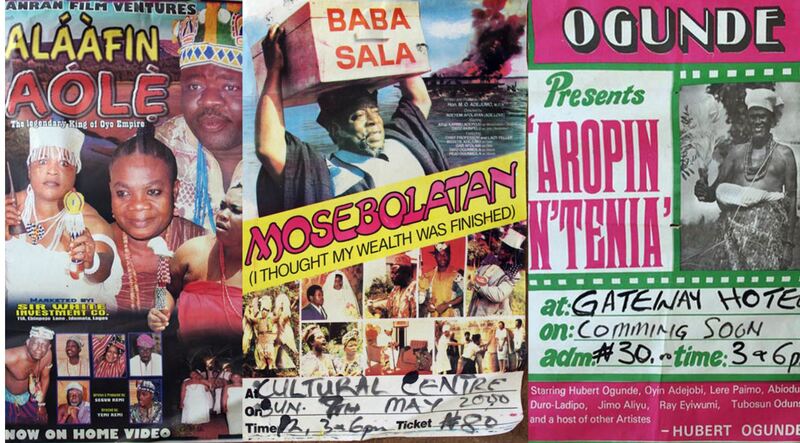

Digital Nollywood is an ongoing digital project established in 2018 to preserve the material history of the film medium in Nigeria, particularly Nollywood, the video-film industry that emerged in the 1990s. Nollywood came into existence after the celluloid tradition of Nigerian cinema collapsed because of the mitigating effects of the structural adjustments that essentially curtailed the production and consumption of cinematic texts. The posters in Digital Nollywood are treated as art objects that offer a rich and alternate history of Nollywood, through visual narratives and exhibitions. In many ways, the project uses movie posters to narrate the story of a media form that tells the African story. Interested in arresting the disappearance of Nollywood's material 'texts,' this project builds on the enormous technological developments of recent decades to explore how we ‘do history’ and explore popular culture in Africa. Based on the affordances of digital media, Digital Nollywood aims to be a scholarly digital project that enables the preservation and exhibition of Nollywood film posters through collections and exhibitions of movie posters on Omeka. The historical documentation of these visual cultural forms adds to the huge scholarship on Nollywood, while also serving to preserve cultural records that may otherwise be lost forever.

Nollywood refers to the Nigerian film industry, which started off as video-film practice after the structural adjustments programs of the late 1980s that wreaked havoc on celluloid production of film in Nigeria. Although a couple of Yoruba video films had been made before it, the 1992 Igbo-language movie Living in Bondage by Kenneth Nnebue, is regarded as the first major film propelled an industry that was later to be named Nollywood by Matt Steinglass in a New York Times article. While Nollywood typically covers English-speaking and Pidgin films, there is a Yoruba component of Nollywood that derives from the Yoruba travelling theatre and its connections to TV and celluloid film, and a separate film industry in Northern Nigeria (Kannywood). Although these aspects of Nollywood have their cultural, and social, and marketing distinctions, new technologies, and digital platforms mean the genres, aesthetics and audiences of filmmaking in Nigeria have increasingly intersected significantly, sometimes under the banner of “New Nollywood.” New Nollywood is supposed to be an iteration of classic Nollywood films that demonstrate sophisticated plot structure and are ideologically and aesthetically solid narratives, although some scholars believe that Old Nollywood describes an ongoing style of production, distribution, and consumption and overlaps with New Nollywood. Nollywood films, both old and new, are distributed on digital platforms such as IrokoTV and Netflix. In 2018 Netflix released its first Nigerian film, “Lionheart” and has recently collaborated with EbonyLife Films in Lagos to adapt Wole Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman for the screen. In recent years, Nollywood has gone from being the leading form of African popular culture to generating other forms of popular culture as it entangles with and is remediated through digital cultures as Internet memes and Gifs.

The goal of Digital Nollywood is the reconstruction of the history of Nollywood through a significant aspect of its material production that is rarely discussed in the scholarly community on postcolonial film and cinema. As the most popular film industry in Africa and the African Diaspora, Nollywood has served as an important platform for telling the African story, highlighting how the culture industry can embody the values, meanings and, identities of groups and communities. A digital archive of film posters on Nollywood enables more historical documentation and academic research on the film medium in the country. Beyond the collection of movie posters in a central online location online, though; this project hopes to foster a more positive disposition toward the process of historical documentation in a country in which the historical record and the past more generally are not accorded the importance they deserve. We are hoping this project will catalyze conversations on the urgency of digitizing the disappearance of Nollywood's production materialities. The digitization of Nollywood movie posters, especially from the era now commonly referred to as old Nollywood, may also initiate a series of activities that will involve Nollywood scholars in the study of film posters for further research.